Why shouldn’t you write your own spin lock implementation

There’s a really good post by Linus Torvalds on why you shouldn’t do it, you can find that here: Link.

But if you don’t really want to read that post, it can be summarized as follows:

- The OS doesn’t understand there’s a spin lock going on, so a spin lock implementation is going to be working against the OS.

- If you have more threads than CPU’s then this gets especially bad because the OS could be context switching from one blocked thread to another

- Yield calls don’t fix this because you can be flooding the OS with scheduling requests

- Locks are a hard problem that people have spent decades researching, what makes you so clever?

- Your lock implementation will almost inevitably have downsides to the scheduling of itself and other processes that it would be better to just use the standard locks since they have been worked on by people over decades to solve those downsides.

Why we’re doing it anyway

Because we don’t need a lock that is optimal in all cases. We need a lock that is optimal in our specific case and our application.

We are not working in a general-purpose environment

This blog is about game development, so let’s break down what are things specific to games.

- The application will run in a single-process with multiple threads

- The number of threads is limited to the number of cores on the machine (or less)

- The application is likely to be the only piece of software the user wants to interact with, and may even be the only front-end application running.

- No tasks on threads are ever long-running. All work needs to be done in a single frame, so an architectural expectation is that any critical sections will have a small footprint.

What concerns do we not care about

Because a game is the user’s focus point. It is a greedy application. I eats up RAM, VRAM, CPU time, GPU time, Disk Space, Everything. It is a special application that users are okay with eating up all the OS’s scheduling time because it’s the thing they’re focused on. All this means that we are allowed to write a lock that messes up the OS’s scheduling, so long as it’s in the name of improving our application’s best interests. Video games are not good neighbors to other processes. We don’t really need the OS to understand we’re locked and it could theoretically schedule another process because we want it to think we’re the top dog process.

We also don’t care about performance for long-running threads with large critical sections. This is not a common thing for games to have, and if you’re going to need those, then I definitely don’t recommend a spin-lock. I’d recommend an event-based architecture that relies on things like std::condition_variable.

What concerns do we care about

We need to make sure our lock has the best throughput for our application. So we need to make sure it has the lowest latency to acquire and release the lock. It also needs to actually work. We want to make sure that, for very small critical sections, we can avoid expensive context switches. Basically we just want high-throughput and avoiding expensive OS calls if possible.

What’s a typical spin-lock implementation

Using std::atomic

Here’s an article to what I think has been the most standard spin-lock implementation I’ve seen Link. What it boils down to is the use of an std::atomic variable and the use of exchange() or compare_exchange(). This is a very reasonable approach and is the standard for writing a lock. It’s using the standard library so it’s portable, and it’s going to work. If it doesn’t work, then the compiler probably has a bug.

Using std::mutex

But why write a lock using the standard libraries if they already have multiple lock implementations like std::scoped_lock, std::unique_lock, and std::shared_lock. Those are very robust lock implementations, portable, feature rich, and they’re standard. This seems even more reasonable than implementing something with std::atomic. It would only seem like a good idea if writing our own lock was faster. And this is indeed the question. Can we write a lock faster than these std locks for our use-case? That’s the important point, we are only benchmarking our own use-case. Not all possible use cases.

Using atomic increments, decrements, adds, and subtracts

There’s an article Here where a spinlock was implemented with std::atomic but used fetch_add(), fetch_or(), and fetch_sub() to implement a lock. It’s an interesting article, and ultimately the thing that stands out is that the performance of the std::atomic fetch_sub() was significantly faster than compare_exchange(). But I wasn’t quite satisfied with the result of the benchmark performed. It just didn’t make sense to me that fetch_add performed so differently than fetch_sub because theoretically, the underlying instructions shouldn’t be that much different. So, my thought was to build a spin lock around atomic increments, decrements, adds and subtracts myself and see what we’re looking at.

The spin lock we’re going to benchmark

Atomics will be managed with their underlying instructions

This might be controversial to some folks, but I’ve never liked std::atomic. It has its advantages, but honestly, I just prefer some good old fashion helper functions to the actual atomic instructions. I think std::atomic is a good interface for creating portable threadsafe variables, but I also think it’s fairly complex to use and I don’t really know what it’s doing behind-the-scenes. And when we’re talking about optimizing a spin lock, we kinda need to know what is going on.

So here is the interface I’m using for our atomic instructions:

uint32_t AtomicIncrementU32(uint32_t& value)

{

return __atomic_add_fetch(&value, 1, __ATOMIC_RELAXED);

}

uint32_t AtomicDecrementU32(uint32_t& value)

{

return __atomic_sub_fetch(&value, 1, __ATOMIC_RELAXED);

}

uint32_t AtomicAddU32(uint32_t& value, uint32_t addend)

{

return __atomic_add_fetch(&value, addend, __ATOMIC_RELAXED);

}

uint32_t AtomicSubtractU32(uint32_t& value, uint32_t subtrahend)

{

return __atomic_sub_fetch(&value, subtrahend, __ATOMIC_RELAXED);

}

uint32_t AtomicAndU32(uint32_t& value, uint32_t mask)

{

return __atomic_fetch_and(&value, mask, __ATOMIC_RELAXED);

}

uint32_t AtomicOrU32(uint32_t& value, uint32_t mask)

{

return __atomic_fetch_or(&value, mask, __ATOMIC_RELAXED);

}

You’ll notice that there’s one thing different about these calls is that we’re using add_fetch and sub_fetch instead of fetch_add and fetch_sub like std::atomic tends to use.

Lock Implementations

There are 3 separate implementations being looked at:

- CountingSpinLock – Prioritizes readers over writers. So the writers must wait for all readers to finish before they can secure the lock. If a reader attempts to join while a writer is working, then they must wait for that writer to finish, but they have a reservation which blocks any other writers from continuing afterwards.

- WritePriorityCountingSpinLock – Prioritizes writers over readers. So the readers do not make reservations while the writer is running, but the first writer will make a reservation that blocks other new readers from starting until the writer is finished.

- MultiReaderWriterCountingSpinLock – A version that allows multiple readers or multiple writers. It’s a weird lock that probably wouldn’t be used in many scenarios, but the idea is that there are some situations where a bunch of writers can be allowed to operate so long as there are no readers, and vice-versa. Read locks are prioritized in this implementation.

One thing you’ve probably noticed is that none of these locks are fair. Either writers are prioritized or readers are. Making the lock fair wouldn’t be too difficult, but doing so would increase the amount of write-calls necessary for the lock to work. The trade-off is that there’s the potential for starvation, but in the context of this article (on games), this realistically wouldn’t happen because all the work to do happens within a frame. The application architecture does not allow long-running tasks or large critical sections. If that’s your situation, then don’t use spin locks, it’s a bad place for them.

Lock Implementation #1 : CountingSpinLock

void CountingSpinlock::AcquireReadOnlyAccess()

{

uint32_t numRetriesLeft = 0xFFFFFFFF;

do

{

uint32_t nextVal = Util::AtomicIncrementU32(lockValue);

if ((nextVal & c_multiReaderWriter_WriteMask) == 0)

{

//No write lock is held, so we can proceed

break;

}

else

{

//A write lock is held, so we need to wait for it to be released

while ((lockValue & c_multiReaderWriter_WriteMask) != 0)

{

//Spin until the write lock is released

std::this_thread::yield();

}

break; //We got it, so break out.

}

--numRetriesLeft;

} while (numRetriesLeft > 0);

}

void CountingSpinlock::ReleaseReadOnlyAccess()

{

Util::AtomicDecrementU32(lockValue);

}

void CountingSpinlock::AcquireReadAndWriteAccess()

{

uint32_t numRetriesLeft = 0xFFFFFFFF;

do

{

uint32_t nextVal = Util::AtomicAddU32(lockValue, c_multiReaderWriter_WriteIncrement);

if (nextVal == c_multiReaderWriter_WriteIncrement)

{

// No read or write locks are held, so we can proceed

break;

}

else

{

// Undo the write-lock increment

Util::AtomicSubtractU32(lockValue, c_multiReaderWriter_WriteIncrement);

// A read or write lock is held, so we need to wait for them to be released

while (lockValue != 0)

{

// Spin until the read and write locks are released

std::this_thread::yield();

}

// Try grabbing it again since there aren't any read or write locks held now

}

--numRetriesLeft;

} while (numRetriesLeft > 0);

}

void CountingSpinlock::ReleaseReadAndWriteAccess()

{

Util::AtomicSubtractU32(lockValue, c_multiReaderWriter_WriteIncrement);

}

Lock Implementation #2 : WritePriorityCountingSpinLock

void CountingSpinlock::AcquireWritePriorityReadOnlyAccess()

{

uint32_t numRetriesLeft = 0xFFFFFFFF;

do

{

uint32_t nextVal = Util::AtomicIncrementU32(lockValue);

if ((nextVal & c_writeLockBit) == 0)

{

//No write lock is held, so we can proceed

break;

}

else

{

//Undo the read-lock increment

Util::AtomicDecrementU32(lockValue);

//A write lock is held, so we need to wait for it to be released

while ((lockValue & c_writeLockBit) != 0)

{

//Spin until the write lock is released

std::this_thread::yield();

}

}

--numRetriesLeft;

} while (numRetriesLeft > 0);

}

void CountingSpinlock::ReleaseWritePriorityReadOnlyAccess()

{

Util::AtomicDecrementU32(lockValue);

}

void CountingSpinlock::AcquireWritePriorityReadAndWriteAccess()

{

uint32_t numRetriesLeft = 0xFFFFFFFF;

do

{

uint32_t prevVal = Util::AtomicOrU32(lockValue, c_writeLockBit);

if (prevVal == 0)

{

//No read or write locks are held, so we can proceed

break;

}

else if ((prevVal & c_writeLockBit) == 0)

{

//No write lock is held, but there are read locks held, so we need to wait for them to be released

while (lockValue != c_writeLockBit)

{

//Spin until the read locks are released

std::this_thread::yield();

}

//All read locks have been released, so we can proceed

break;

}

else if ((prevVal & c_writeLockBit) != 0)

{

//A write lock is held, so we need to wait for it to be released

while ((lockValue & c_writeLockBit) != 0)

{

//Spin until the write lock is released

std::this_thread::yield();

}

}

--numRetriesLeft;

} while (numRetriesLeft > 0);

}

void CountingSpinlock::ReleaseWritePriorityReadAndWriteAccess()

{

Util::AtomicAndU32(lockValue, ~c_writeLockBit);

}

Lock Implementation #3 : MultiReaderWriterCountingSpinLock

void CountingSpinlock::AcquireMultiReaderWriterReadAccess()

{

uint32_t numRetriesLeft = 0xFFFFFFFF;

do

{

uint32_t nextVal = Util::AtomicIncrementU32(lockValue);

if ((nextVal & c_multiReaderWriter_WriteMask) == 0)

{

//No write locks are held, so we can proceed

break;

}

else

{

//A write lock is held, so we need to wait for it to be released

while ((lockValue & c_multiReaderWriter_WriteMask) != 0)

{

//Spin until the write lock is released

std::this_thread::yield();

}

break; //No write locks are held, so we can proceed

}

--numRetriesLeft;

} while (numRetriesLeft > 0);

}

void CountingSpinlock::ReleaseMultiReaderWriterReadAccess()

{

Util::AtomicDecrementU32(lockValue);

}

void CountingSpinlock::AcquireMultiReaderWriterWriteAccess()

{

uint32_t numRetriesLeft = 0xFFFFFFFF;

do

{

uint32_t nextVal = Util::AtomicAddU32(lockValue, c_multiReaderWriter_WriteIncrement);

if ((nextVal & c_multiReaderWriter_ReadMask) == 0)

{

//No read locks are held, so we can proceed

break;

}

else

{

//Undo the write-lock increment

Util::AtomicSubtractU32(lockValue, c_multiReaderWriter_WriteIncrement);

//A read lock is held, so we need to wait for it to be released

while ((lockValue & c_multiReaderWriter_ReadMask) != 0)

{

//Spin until the read lock is released

std::this_thread::yield();

}

}

--numRetriesLeft;

} while (numRetriesLeft > 0);

}

void CountingSpinlock::ReleaseMultiReaderWriterWriteAccess()

{

Util::AtomicSubtractU32(lockValue, c_multiReaderWriter_WriteIncrement);

}

Benchmarking Code

For all the benchmarks, I’m using scoped versions of locks since it’s more common in practice than calling Lock/Unlock calls. I’m using GTest as the interface for running all the benchmarking code.

Test Code Structure

The tests themselves all are structured something like the following:

TEST_F(SpinLockWriteHeavyTest, StdMutex_AllWrites_MultiThread)

{

std::mutex mtx;

uint64_t counter = 0;

auto writeOperation = [&mtx, &counter](uint32_t) {

std::scoped_lock lock(mtx);

SpinLockBenchmarkTest::SimulateWork();

++counter;

};

RunWithThreadCount<16>("StdMutex_AllWrites_MultiThread", writeOperation, OPERATIONS_PER_THREAD);

ASSERT_EQ(counter, OPERATIONS_PER_THREAD);

counter = 0;

RunWithThreadCount<8>("StdMutex_AllWrites_MultiThread", writeOperation, OPERATIONS_PER_THREAD);

ASSERT_EQ(counter, OPERATIONS_PER_THREAD);

counter = 0;

RunWithThreadCount<4>("StdMutex_AllWrites_MultiThread", writeOperation, OPERATIONS_PER_THREAD);

ASSERT_EQ(counter, OPERATIONS_PER_THREAD);

counter = 0;

RunWithThreadCount<2>("StdMutex_AllWrites_MultiThread", writeOperation, OPERATIONS_PER_THREAD);

ASSERT_EQ(counter, OPERATIONS_PER_THREAD);

counter = 0;

RunWithThreadCount<1>("StdMutex_AllWrites_MultiThread", writeOperation, OPERATIONS_PER_THREAD);

ASSERT_EQ(counter, OPERATIONS_PER_THREAD);

}

Simulating a workload

The SimulateWork function looks like this:

static void SimulateWork()

{

volatile uint64_t dummy = 0;

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < WORK_CYCLES; ++i)

{

dummy = dummy + i;

}

}

Running on Multiple Threads

The RunWithThreadCount function looks like this:

template<uint32_t NUM_THREADS>

static void RunWithThreadCount(const char* testName, auto&& testLogic, uint64_t expectedCount)

{

using ThreadPoolType = PklE::MultiThreader::WorkerThreadPool<1, NUM_THREADS, 1, 500, 64>;

ThreadPoolType pool;

typename ThreadPoolType::ThreadDistribution distribution;

distribution[0] = 16;

typename ThreadPoolType::ThreadDistribution balanced = pool.DistributeThreads(distribution);

pool.StartThreads(balanced);

auto start = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

const uint32_t c_maxTasks = 64;

const uint32_t c_elementsPerTask = 25;

const bool bCallingExternally = true;

pool.template RunParallelForInRangeInQueue<c_maxTasks>(0, OPERATIONS_PER_THREAD, 0, testLogic, c_elementsPerTask, bCallingExternally);

auto end = std::chrono::high_resolution_clock::now();

auto duration = std::chrono::duration_cast<std::chrono::nanoseconds>(end - start);

char fullTestName[256];

snprintf(fullTestName, sizeof(fullTestName), "%s_%dThreads", testName, NUM_THREADS);

auto result = CreateResult(fullTestName, duration, expectedCount);

result.Print();

}

You’ll see some stuff in there about a custom thread-pooling implementation. You can choose to believe me on whether or not you think that works, but it’s something else I set up that I might write an article about later.

Benchmarking Results

Tests

There were 5 tests run for each lock type. For each test they were tested on a scaled number of threads from 1 to 16 incrementing in powers of 2. These were all run on a 16 core machine hosted through GitHub Codespaces. For each test, I ran it 5 times and averaged the results to try and reduce any kind of random errors introduced by individual runs.

The tests are as follows:

- AllReads – The locks were only used in a read-only way

- AllWrites – The locks were only used to lock a writable critical section

- 90Read10Write – 90% of the locking operations were read-only

- 50Read50Write – Half the locking operations were read-only

- 25Read75Write – 25% of the locking operations were read-only

The locks benchmarked are as follows:

- StdMutex – a standard std::mutex locked used std::scoped_lock

- StdUniqueShared – a std::shared_mutex locked using std::shared_lock and std::unique_lock depending on read/write access

- Rigtorp – the custom spin lock implementation from here.

- CountingSpinLock – Described above in the lock implementation #1 section

- WritePriorityCountingSpinLock – Described above in the lock implementation #2 section

- MultiReaderWriterCountingSpinLock – Described above in the lock implementation #3 section

Result Graphs

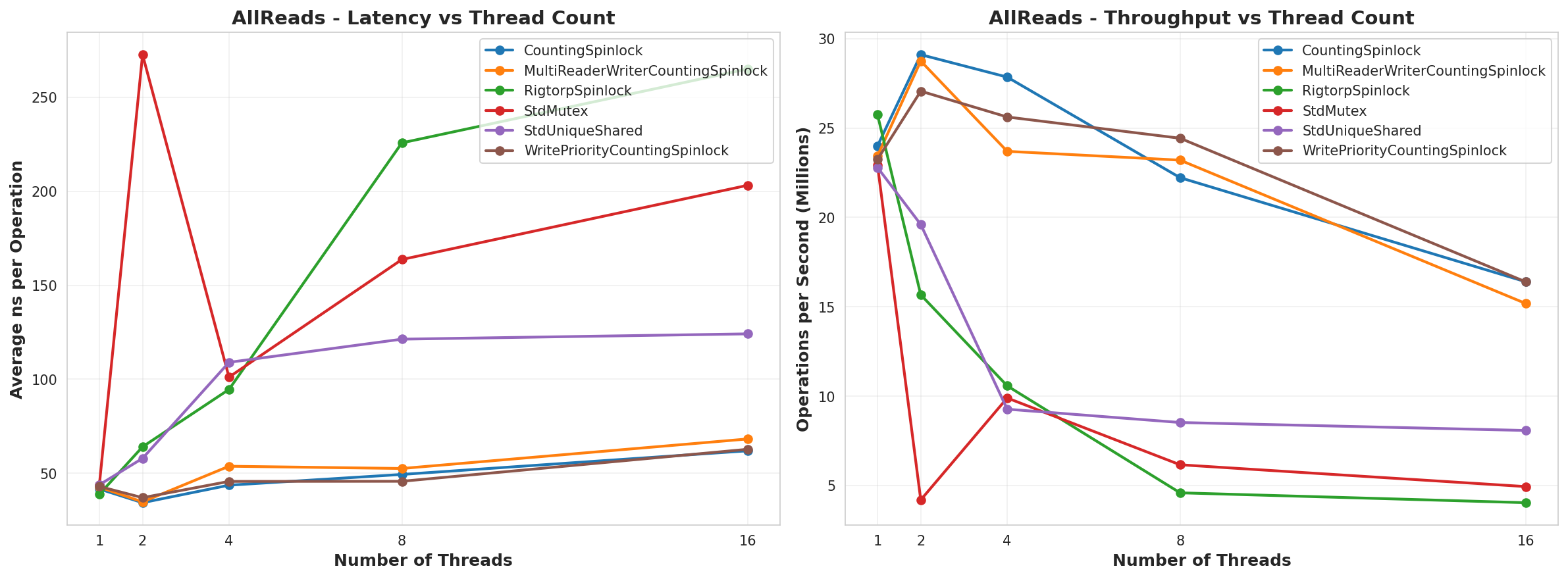

All Reads

All Writes

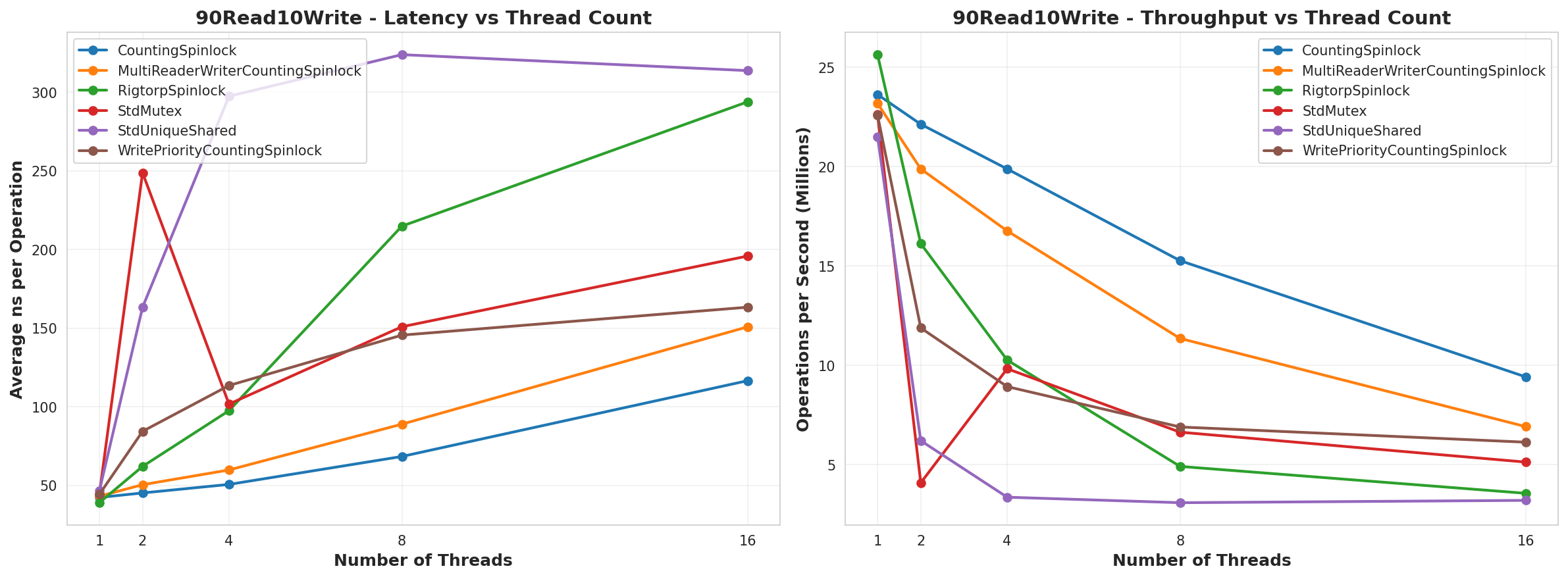

90% Reads, 10% Writes

50% Reads, 50% Writes

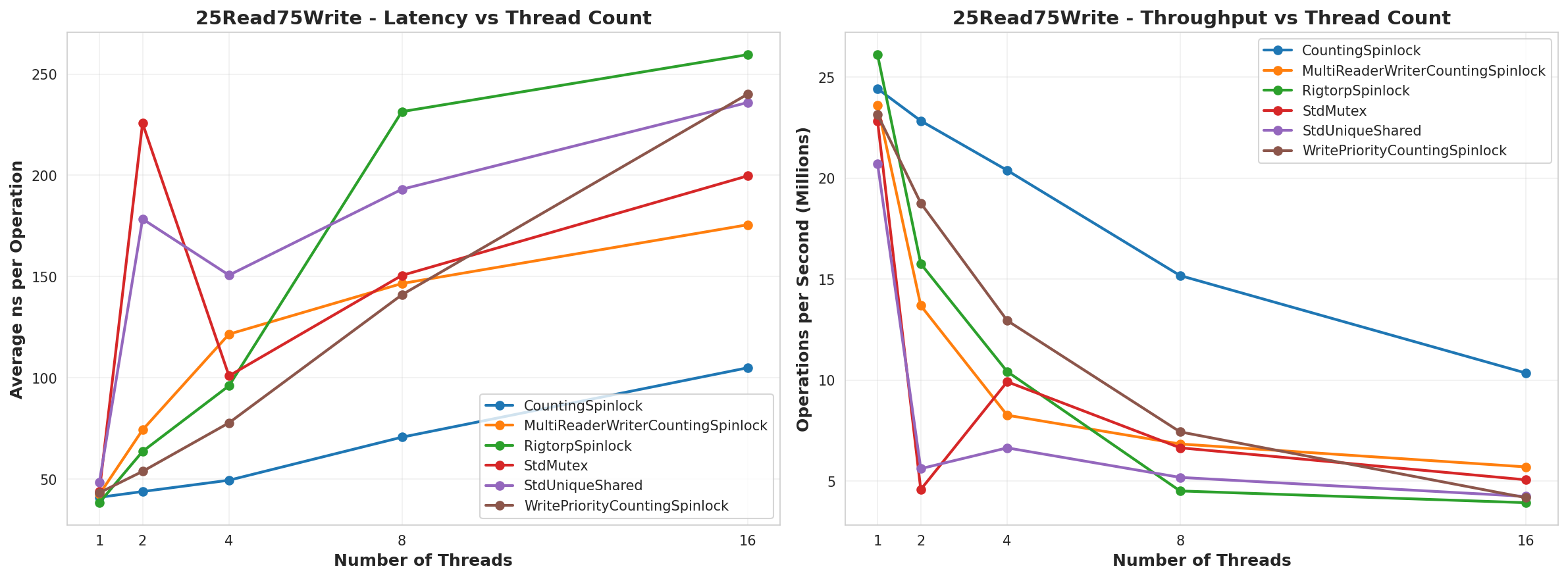

25% Reads, 75% Writes

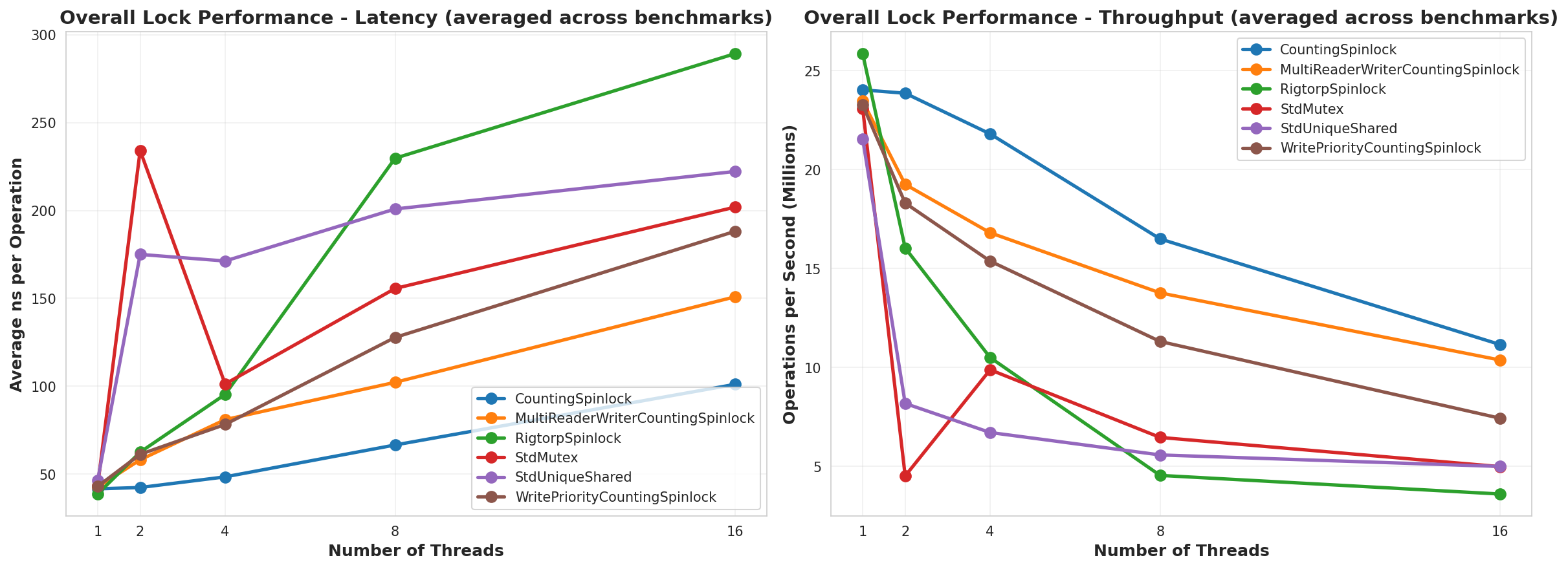

Overall Average

Summary

So, from this test, it looks like the CountingSpinLock ran better than everything. The only place where it didn’t appeared to be when it was All Writes and then the MultiReaderWriter won over, which makes sense since it’d be the only lock that was actually running in parallel. I would have expected it to also run faster than the CountingSpinLock in the 25Read75Write test, but my guess is that, since it’s a reader prioritized lock, it never got the lock as often as it needed. The other piece of this is that the MultiReaderWriter had to run. Of note as well, is that in the AllWrites test, the WritePriority lock vs the regular CountingSpinLock used an atomic OR and AND operation instead of incrementing and decrementing. That is probably why it has such lower performance. I think I’d replace that to use an add and subtract like the others to have better performance.

Why does CountingSpinLock do so well in this benchmark compared to the others?

I think there’s a few reasons for this.

One reason would be that the standard locks are trying to be true general purpose locks that are guaranteed to work across all platforms. They seek best performance across a wide variety of benchmarks. They will attempt to work with the operating system to be fair for all processes and threads. And for all they need to do, they are performing really really well. Again, I would use those lock implementations for any long-running tasks or large critical sections. But they are sub-optimal for a single process, thread counts close to the CPU count, and small critical sections.

Another reason is that CountingSpinLock is using a relaxed memory ordering while implementations involving compare-exchange need to specify stricter memory ordering because that order matters. This matters because it affects how the processor will optimize the cache. Because we’re using adds and subtracts, the order of the instructions doesn’t matter, so long as the result we get is the correct result at that moment, and that’s guaranteed (only the order of the instructions is not). Once we have that result, we’ll be accessing that cached version until another atomic operation clears that cache value. This means the spin-wait is cheap since it won’t mark the cache dirty, and the processor and compiler can optimize the cache use as much as possible.

When would I expect CountingSpinLock to perform like garbage

I expect it to work terribly for any long-running critical section. I expect it to work terribly if you have way more threads than CPUs. It also is not a nested lock, so if a thread takes the lock, then invokes another function that also attempts to take the lock, you can get a deadlock. This is meant to be a high-performance way to manage small critical sections.

Where is the code?

It’s on GitHub here:

https://github.com/PickledMonkey/CountingSpinLockBenchmark

Of note is that the code is not packaged to compile or anything. It’s mostly just snippets I pulled so that it can be pulled into whatever development environment you’re working in. In this age of AI coding, you could probably ask an AI to pull the repo and integrate the code if you wanted.

References used when making this article

Links:

https://mmomtchev.medium.com/spinlock-vs-mutex-performance-3f73de53a460

https://www.realworldtech.com/forum/?threadid=189711&curpostid=189723

https://dev.to/agutikov/who-is-faster-compareexchange-or-fetchadd-1pjc