I was recently playing a neat VR game called Sairento VR. It’s a cool game where you play a kick-butt cyber-ninja-lady, but there was one thing that was a bit off-putting for me. The enemies all executed the same canned animations whenever they attacked you. For shooting a gun, that’s fine, but it was really awkward in melee encounters. Even though you knew they were just repeating the same animation, it was hard to react to. I think the problem is because they never adjusted the animation to react based on how you, the player was positioned. So, I thought to myself, how can you make an adversary in VR that seems to react based on how the player is poised? Then I put together a little experiment.

Setting up the Test Environment

The first step was to make a test bed for experimenting with an AI. So I put together a simple game.

The player just has to touch a small floating block in the center of the room; everytime you do, you get a point. However, there is a floating “Paddle” controlled by an AI. If the AI paddle touches your hand, you were “blocked” and the AI gets a point. The goal of the AI is to minimize the points the player earns while maximizing the points it earns. However, the AI’s challenge is that it only has 3 potential movement options, Attacking, Defending, and Stopping.

AI Movement Attacking

The Attacking movement is simple. The Paddle will simply charge toward the player’s hand as fast as it can. The problem with this approach is that the player can just dodge the attack and the AI will take a long time turning around to re-engage.

AI Movement Defending

The Defending movement is also pretty simple. The AI will simply try to sit between the player and the target. The downside is that it can’t move as fast as Attacking.

Stop Movement

The stop movement is meant to compliment the other two behaviors. To help the AI deal with getting launched far away, it can stop itself at anytime to change direction.

When the Stop movement is combined with attacking, the AI becomes extremely aggressive, and the player needs to keep moving to avoid getting hit. However, it’s still really predictable and as long as you’re moving you’re not going to get hit.

When the Stop movement is combined with defending, it helps the AI keep up with the player, but it’s still not enough. The player can still move faster than the AI, and it can be tricked to move off to the side to allow the player access to the target. For the AI to really be effective, it needs to still go on the offensive when it has an opening.

Putting It Together for a Basic AI State Machine

Obviously, each of these actions won’t pose much of a challenge for the player by themselves, so the next course of action is to just put it all together in a simple state machine to see how it acted.

The state machine is based off the AI’s Time to Collision (ttc) with the Player’s hand and the AI’s distance from the Player’s hand. If the ttc is negative, then that implies the Paddle is moving away from the player’s hand, so it stops. Otherwise it will defend until the player’s hand is close enough to attempt an attack.

This behavior is a lot more interesting than the previous examples. However, it still has the same problem of being very predictable. Once the player figures out the sweet spot to avoid getting hit, they can do the same action every time. What needs to happen, is the AI needs to learn certain patterns the player tends to follow.

Adding Weights to State Transitions

The next idea is what if there’s some way to supersede the default logic when the player might be trying to trick it. That would allow the AI to react in a trickier way, and the player might find it more engaging.

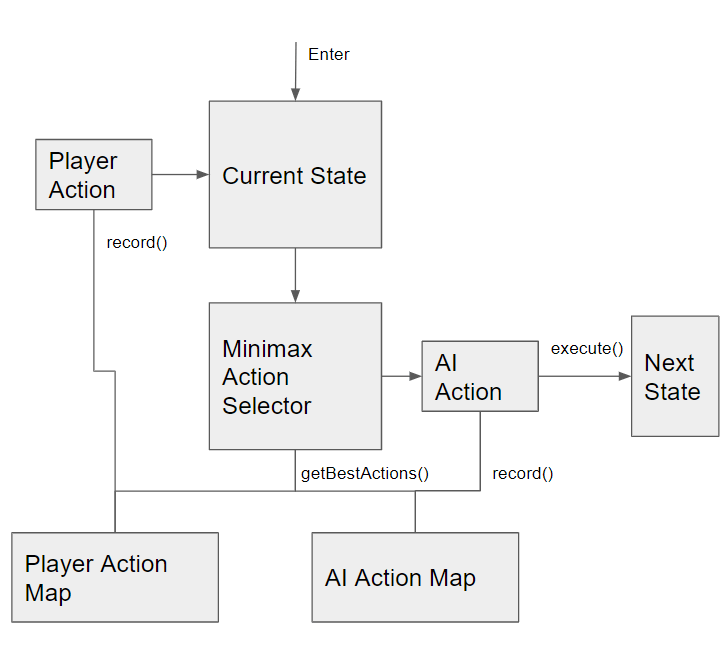

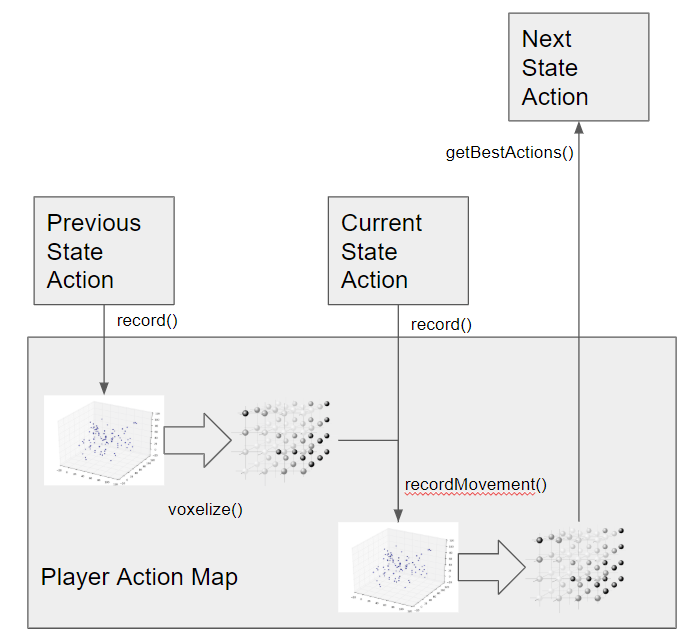

However, adapting to the player’s behavior implies some sort of way to record what’s been happening and what the outcome was. To start, I broke down the game into a state structure to describe what’s going on at a single moment. I chose the state to be a combination of the location and velocity of the player’s hand and the paddle. This makes a state space that contains plenty of information at each state, but has the downside of being too granular to be useful. To solve that problem, I just rounded the values for each state into a set a state “voxels” and used a KD-Tree for storing the state history.

The purpose of storing a state history is that we can also store what action was chosen by the AI at that particular state and adjust a weight on that particular action based on whether it led to the AI or player scoring a point.

In practice this actually kinda worked okay. The AI responded differently as the player got more points, and it made for a much more challenging game. In this particular example it was interesting because as the game went on, the AI just became more aggressive and would attack more often when you tried to trick it. The AI also isn’t acting with any kind of high level plan or really any anticipation of what the player will do next; it’s simply trying something different because the last time led to failure. So, the next step is to give it some kind of higher level decision making.

Applying Mini-Max to the AI Agent

To give the AI some higher level planning, I went towards applying the mini-max algorithm to it. However, mini-max is normally used in games that have finite state spaces with a finite set of actions because for it to make the best decisions it involves performing a full traversal of the entire action-state space to make a decision. This is problematic when we’re operating in a state space that is essentially infinite. To get around this, I spun out the mini-max traversal to a separate thread and put a timer on it so it just gives a best-effort decision periodically.

Similar to how the AI’s state and actions were recorded into a history, the player’s state and actions were also voxelized. However, since the player isn’t constrained to a specific set of actions, an action for the player is recorded as which state it transitioned to.

When it all comes together, it creates very different behavior than the previous examples.

Rather than fall for the same tricks, this AI made some new behavior and would start creeping up on the player before attacking. This behavior is interesting to observe, but it might be irritating for a player to deal with. In this version, the AI is a lot less predictable, which can seem unfair for a player. In the end though, it could probably be expanded to create a really engaging AI opponent.

Applying this back to Animations in VR

While this example is being applied to a simple game, there’s a lot of potential to bring this into a larger game. For example, this kind of agent system could be applied to a hand using IK bones to maneuver a sword for a melee attack. The overall goal would be encounters that seem less stiff and scripting, and more dynamic to the player’s interaction.

Code Location

Code available on GitHub here: https://github.com/PickledMonkey/Learning_AI_for_VR